!For English Scroll down!

Juliette GOIFFON (1987) & Charles BEAUTE (1985) sont diplômés des arts-décoratifs de Strasbourg et des beaux-arts de Paris.

Ils vivent et travaillent entre Paris et Lyon.

Juliette Goiffon et Charles Beauté « Continuous Improvement »

Qu'il s'agisse du métier à tisser, de la chaîne d'assemblage ou dans, une certaine mesure, de l'ordinateur, tous ces outils de production comportent un aspect intrinsèquement rassurant. Pourquoi ? Parce qu'il nous sont extérieurs. Ces machines, une fois la journée de labeur accomplie, nous pouvons leur tourner le dos.

Sur l'échiquier d'une vie moderne sans aspérités, efficace et climatisée, l'humain se meut sans encombres. Dans un rêve parfaitement corbuséen, nous délaisserions la zone dévolue au travail pour nous diriger vers la zone de loisirs, puis la quitterions pour la zone domestique - celle de la récupération de la force de travail.

Pour utopique qu'il soit, ce fantasme de la séparation spatiale entre les activités persiste également dans la description synchronique que fait Marx de la société communiste idéale : le règne de la liberté commence lorsque l'homme est à même de s'échapper de la sphère de production matérielle proprement dite, lorsque la satisfaction des besoins naturels, nécessaires à la conservation et à la reproduction de la vie, se fait dans le cadre d'une journée de travail réduite laissant suffisamment de place aux activités de l'esprit à sa suite.

Pourtant, à l'orée du siècle qui s'inaugure, ces considérations semblent bel et bien en voie d'être définitivement dépassées. Non pas que les progrès technologiques aient rendu le travail dispensable.

Au contraire, nous sommes entrés dans l'ère de la symbiose : nous sommes devenus nous-mêmes des êtres composites, fusionnant avec l'outil de production. Ce devenir-chair de la production repose sur un paradoxe. Comme si l'on retournait l'arme contre nous, le travail est devenu travail sur soi, et le corps à la fois moyen et fin.

Ce dont il s'agit ici est de la course à l'optimisation effrénée de nos propres capacités. Car l'avènement du travailleur indépendant n'a pas que des avantages : devenu sa propre marque, forcé à être toujours plus inventif, flexible et disponible, le travailleur du futur – et le futur s'amorce déjà – est devenu son propre produit. Comme les rutilants bien de consommation que ses ancêtres manufacturaient à la chaîne, étudiés pour appâter le plus efficacement possible l'acheteur, le travailleur du futur se doit lui-aussi d'être le plus attrayant du rayonnage.

Ce sont ces mutations qui infusent le cycle de trois expositions conçu par le duo Juliette Goiffon et Charles Beauté. Initié lors de la 66e édition de Jeune Création, où ils présentaient « 'x' hours before deadline », une installation évoquant un futur espace de travail potentiel, il se clôturera cet été avec un volet consacré au management au Centre d'art la Halle des Bouchers à Vienne.

A la Galerie Eva Meyer, l'exposition Continuous Improvement montre ce à quoi pourrait donner naissance cette logique de développement intensif de soi dans un futur proche. Basée sur le rapport au corps, Continuous Improvement prend ainsi la forme d'un environnement à mi-chemin entre l'espace de travail collectif et la salle de sport individuelle.

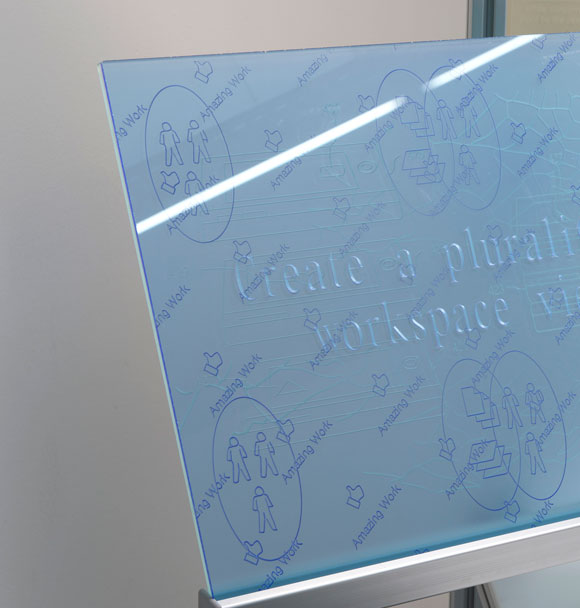

Au mur, des miroirs colorés sont gravés de slogans positifs : « Today, you are you. There is no one alive who is you-er than you », lit-on. Ou encore : « One small step can change your life ». Ces messages placidement tautologiques se détachent sur fond d'informations chiffrées et de motifs géométriques.

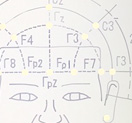

En s'éloignant, on se rend compte que ceux-ci constituent des visages primitifs, les mêmes que l'on retrouve plus loin sous forme de masques de laiton, ainsi que gravés sur les tapis sous nos pieds.

Ces visages qui nous fixent, yeux et bouche béants, sont réduits aux fondamentaux - ceux qui, à partir d'un minimum de référents, nous font spontanément reconnaître une forme humaine. Frappés de lettres et de chiffres à certains endroits, fragmentés en parties distinctes, ils dotent la rentabilisation à outrance d'une apparence.

Pour réaliser les masques, le duo s'est basé sur des dessins brevets de liftings et d'électrostimulateurs accessibles via le moteur de recherche Google Patent Search. Tels des effigies de dieux primitifs, ces faciès augmentés témoignent d'une nouvelle religion, plus monothéiste que jamais, puisque c'est dès lors à soi-même que s'adresse le culte : ce culte, pour reprendre le terme du philosophe Boris Groys, est celui de l' « autodesign ».

Or précisément, ce nouvel avatar de l'ultra-libéralisme trouverait notamment sa préfiguration dans l'artiste et ses manières de produire, représentant une frange expérimentale du néolibéralisme, à la fois victime et exemplification de ses dérives. C'était notamment la thèse de Luc Boltanski et d'Eve Chiapello dans leur séminal ouvrage « Le Nouvel Esprit du Capitalisme » (1999), reprise et augmentée par Pierre-Michel Menger dans « Portrait de l'artiste en travailleur » (2003).

Pour Juliette Goiffon et Charles Beauté, la réflexion sur le travailleur du futur ne s'incarne pas uniquement dans des représentations : elle s'invente à mesure qu'elle se construit, à même la matière. En témoigne la volonté d'avoir recours à la gravure directe, pour laquelle il leur a fallu mettre au point une technique nouvelle et construire une machine. Par ce procédé, rien n'est imprimé, rien ne s'ajoute par superposition, rien n'est extérieur à la matière-corps. Les schémas et les encouragements affleurent à même la membrane sensible, faisant résonner la proximité sémantique de « design » et « dessin » : à même la peau, chacun porte le mapping de son propre avenir radieux.

Ingrid Luquet-Gad, février 2016

ENGLISH

Whether it is the loom, the assembly line or, to a certain degree, the computer, all these production tools have an intrinsically reassuring aspect. Why? Because they are outside us. These machines, once they have accomplished their work day, we can turn our backs on them.

In a modern life without any rough edges, efficient and air-conditioned, the human being moves about without any mishaps. In a perfectly Corbusian dream, we leave the zone devoted to work to go to the leisure zone, then we would leave it for the home zone – that of recuperation of the labour power.

As utopian as it seems, this fantasy of the spatial separation between activities also persists in the synchronic description that Marx formulated of the ideal communist society: the reign of freedom begins when man is in a position to escape the material production sphere properly speaking, when meeting natural needs, necessary to preserve and reproduce life, is done in the framework of a reduced workday leaving enough room for intellectual activities afterward.

However, at the dawn of the century that is beginning, these considerations clearly seem on the road to being definitively left behind. Not that technological progress has made work dispensable. On the contrary, we have entered the era of symbiosis: we have become ourselves composite beings, merging with the production tool. This becoming the flesh of production is based on a paradox.

As if we turned the weapon against ourselves, work has become work on oneself, and the body both the means and the end. The idea here is the race to a frenzied optimization of our own capacities. Because the arrival of the independent worker has not brought with it only advantages: having become its own brand, forced to be ever more inventive, flexible and available, the worker of the future – and the future has already begun – has become his own product.

Like the shiny consumer goods that his ancestors manufactured on the assembly line, studied to lure the buyer as efficiently as possible, the worker of the future owes it to himself to be the most appealing on the shelf.

It is these mutations that permeate the cycle of three exhibitions designed by the duo Juliette Goiffon and Charles Beauté. Initiated at the 66th session of Jeune Création, where they presented “‘x’ hours before deadline,” an installation evoking a future potential workspace, it will close this summer with a section devoted to the management of the art center La Halle des bouchers in Vienne.

At the Galerie Eva Meyer, the exhibition “Continuous Improvement” shows what this intensive self-development logic could give birth to in the near future. Based on the relationship to the body, “Continuous Improvement” takes the form of an environment halfway between the collective workspace and the individual gym.

On the wall, colored mirrors are engraved with positive slogans: “Today, you are you. There is no one alive who is you-er than you,” we can read. And: “One small step can change your life.” These placidly tautological messages stand out against a background of numerical data and geometric motifs. Standing at a distance, we realize that they comprise primitive faces, the same ones that are found farther on in the form of brass masks, as well as faces engraved on the carpets under our feet.

These faces, which stare at us, eyes and mouth wide open, are reduced to the basics – those who, starting with a minimum of references, spontaneously make us recognize a human form. Struck with letters and numbers here and there, fragmented into distinct parts, they endow excessive profitability with an appearance.

To make the masks, the duo used patent drawings of facelifts and electrostimulators accessible via the Google Patent Search search engine. Like effigies of primitive gods, these enhanced facies bear witness to a new religion, more monotheistic than ever, since the cult is addressed to oneself: this cult, to use the term of the philosopher Boris Groys, is that of “autodesign.”

Yet in fact, this new avatar of ultra-liberalism could notably find its prefiguration in the artist and how he or she produces, representing an experimental fringe of neoliberalism, both viction and exemplification of its aberrations. This was notably the thesis of Luc Boltanski and Eve Chiapello in their seminal work “Le Nouvel Esprit du Capitalisme” (1999), taken up and expanded by Pierre-Michel Menger in “Portrait de l'artiste en travailleur” (2003).

For Juliette Goiffon and Charles Beauté, the reflection on the worker of the future is not solely incarnated in representations: it is invented as it is built, right from the material. This is shown by the desire to use direct engraving, for which they had to develop a new technique and build a machine.

Nothing is printed through this process, nothing is added by superimposition, nothing is exterior to the material-body. The systems and encouragements directly touch the sensitive membrane, making the semantic proximity of “design” and “drawing” resonate: right on the skin, each individual bears the mapping of his own radiant future.

Ingrid Luquet-Gad, February 2016